By: Erica Lau

Knowledge to Practice: The Struggle is Real

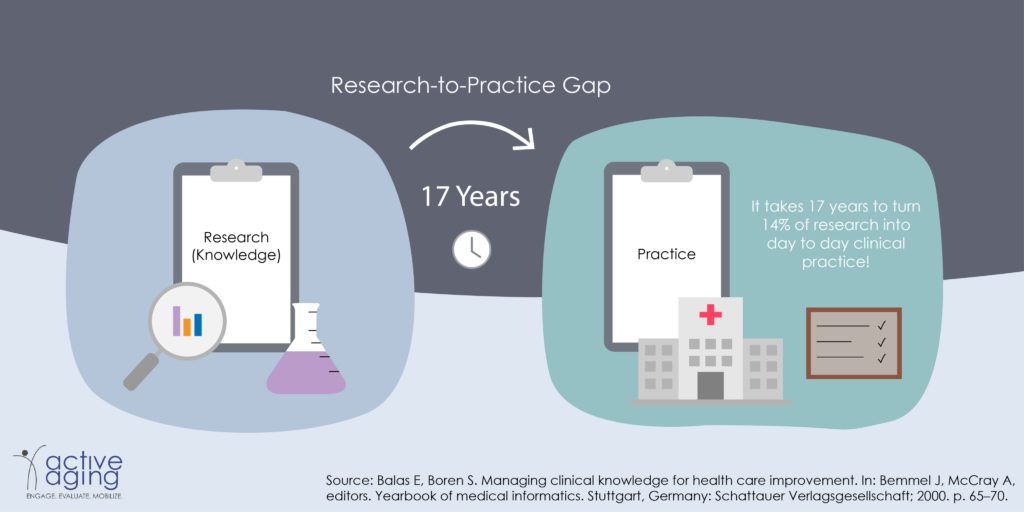

We see thousands of health research articles published every month. However, there is a gap between research-to-practice. It takes 17 years to turn only 14% of research into day-to-day clinical practice (1). To benefit the health of the population, we need to make use of research findings in a timelier manner. Therefore, it is important to find a solution to reduce this gap. A growing area of study, Implementation Science, could be the key (2).

Implementation science is, “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practices, and hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.”(3)

While this field has grown rapidly over the past two decades, implementation science is still not well understood (4). One of the reasons could be that there are many theoretical concepts that guide implementation, and these concepts are often named, defined, and classified inconsistently in the literature (5). For a newbie, or even a seasoned scientist, this can be confusing. Still, this is a much needed and growing area of study. For those who would like to enter this murky field, and do not know how to navigate the nomenclature, let me recommend beginning with “implementation.” This is the first and most important concept that you should learn.

Let’s Define Implementation

In the academic world, we define implementation as the “process of putting to use or integrating evidence-based interventions within a setting. (6)” ‘The process,’ is often a set of planned activities that help individuals to put a program in place, such as a training or coaching initiative, or the provision of intervention materials (e.g., program manual). Like a video demonstration or a recipe that teaches people how to make a dish.

Three Reasons Why You Should Care About Implementation

1. Opening the “Blackbox”

Back in the day, before implementation as a field of study emerged, many published articles described the intervention, and then explored the effect or impact of the intervention. Little was written about how the intervention worked. Of course, we know that the invention was not magically generated– thought and planning always went into the delivery of an intervention. Without capturing the how, the reader may never know the true reason why an intervention was successful or not. Information about program implementation is essential for advancing our knowledge of how to effectively intervene, adapt, replicate, and sustain evidence-based interventions (7–10). This is similar to detailing the process of how you turn a bunch of ingredients into an apple pie.

2. Why Did it Work (or not)? Was it the Program or the Process…?

When implementation is captured in the literature, we can interpret program effectiveness more accurately. For example, let’s say we evaluated a 12-week intervention for impact and process. We observed that the intervention had owed no effect on improving physical activity levels, but the process data showed that only 50% of the intervention modules were implemented. Without considering implementation data, we may erroneously conclude that the program is ineffective when, in fact, the insignificant outcomes are a result of poor program delivery (7, 10).

3. May the Odds be Ever in your Favour: Achieving Positive Program Outcomes

Optimal levels of implementation increase the odds of achieving positive program outcome 6 to 12 fold (8). What does optimal mean? A commonly used threshold is 60%. Simply put, if you implemented at least 60% of a program (e.g., six out of the 10 planned program activities), you are more likely to attain a positive program outcome. It is important to note that this threshold may vary depending on types of interventions and many other factors. More studies are needed to strengthen the evidence base.

Finally, How Exactly is Implementation Measured?

We use ‘implementation outcomes’ as indicators of program implementation. Implementation outcomes are, “effects of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new treatments, practices, and services. (5)” As mentioned earlier, implementation is a process that often includes a set of planned activities that help individuals to put a program in place. Essentially, we want to determine the success of these planned activities.

The literature suggests approximately ten implementation outcomes: adoption, acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration, sustainability, reach and dose delivered. You may find detailed descriptions of these implementation outcomes in Proctor et al (5) and McKay et al (11).

Although researchers generally agree on what are the implementation outcomes, the field is still far away from being able to validly measure them. One reason is that these implementation outcomes may be named, defined, and classified differently across sectors (12). For example, ‘reach’ (public health) and ‘coverage’ (global health) both refer to the proportion of the intended audience (e.g., individuals or organizations) who participate in an intervention. Another reason is that many researchers devise “home-grown” tools and pay little attention to measurement rigour (13). Measures and tools are currently being developed to assess different implementation outcomes in the health promotion sector (14–16). However, producing standardized, valid and reliable tools in a context-driven, dynamic science is a challenge.

In summary, implementation science is a key to bridging the research-to-practice gap. Many intervention researchers are eager to learn more about it. However, this is a rather murky field as there are a maze of theoretical concepts that are used and measured differently across sectors. This article introduced the first and most important concepts in implementation science — program implementation. Hopefully, this is a good starting place for you.

References

Balas E, Boren S. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray A, editors. Yearbook of medical informatics. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft; 2000. p. 65–70.

Fixsen D, Blase K, Naoom S, Metz A, Sims B, Van Dyke M. Evidence-based programs: a failed experiment or the future of human services? 2012.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science. 2006;1(1):1.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32-.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP. 2008;14(2):117–23.

Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT. The Study of Implementation: Current Findings From Effective Programs that Prevent Mental Disorders in School-Aged Children. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2000;11(2):193–221.

Durlak J, DuPre E. Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50.

Durlak JA. Why Program Implementation is Important. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 1998;17(2):5–18.

Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(1):23–45.

McKay H, Naylor P-J, Lau E, Gray SM, Wolfenden L, Milat A, et al. Implementation and scale-up of physical activity and behavioural nutrition interventions: an evaluation roadmap. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2019;16(1):102.

Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(34):462–80.

Proctor EK, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernandez D, Garcia-Corpas JP, Kenny P, Benrimoj SI. Development and testing of two implementation tools to measure components of professional pharmacy service fidelity. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(3):369–77.

Lewis CC, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Fischer SM. Advancing implementation science through measure development and evaluation: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2015;10:102.

Rabin BA, Lewis CC, Norton WE, Neta G, Chambers D, Tobin JN, et al. Measurement resources for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implement Sci. 2016;11:42.